Last updated August 1, 2018 at 10:19 am

Think heatwaves on land are getting bad? It’s nothing compared to what’s happening under the sea.

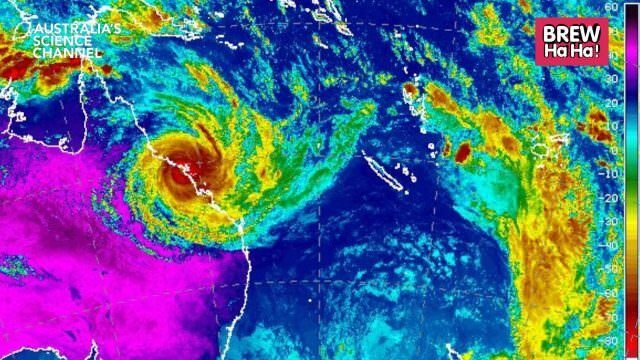

The increasing number, intensity and duration of marine heatwaves is likely to have a profound impact on ocean ecosystems and the industries, like fisheries and tourism, that depend on them. Credit: Daniel Hjalmarsson (Unsplash.com)

An international study has found that marine heatwaves are getting longer, more frequent and hotter, and that spells bad news for not only the fish, but for us too.

The research, which involved Australian researches from the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes (CLEX) and the Institute of Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS), found that since 1925, the frequency of marine heatwaves had increased on average by 34% and that they were lasting 17% longer.

Added together, this means there has been a 54% increase in the number of marine heatwave days every year.

Even more worryingly, it seems this change is increasing.

“Our research also found that from 1982 there was a noticeable acceleration of the trend in marine heatwaves,” said Dr Eric Oliver from Dalhousie University in Canada, who led the research.

The importance of the oceans

When we’re at the beach we might enjoy slightly warmer water, however, for things that live under the water changes in temperature can be disastrous.

A few degrees either way can drastically affect entire ecosystems and biodiversity, which has flow on effects for fisheries, tourism and aquaculture. If life under the surface starts struggling, our economy will too.

In 2011, Western Australia saw a marine heatwave that shifted ecosystems from being dominated by kelp to being dominated by seaweed. That shift remained even after water temperatures returned to normal.

Tasmania’s intense marine heatwave in 2016 led to disease outbreaks and slowing in growth rates across aquaculture industries.

There has also been the high-profile die-offs of coral through the Great Barrier Reef, with some regions experiencing bleaching to 70% of corals. However, despite corals being the poster child victims, the damage goes much further.

To find this change in heatwaves, the researchers combined satellite data with a range century long datasets taken from ships and various land based measuring stations. They then removed the influences of natural variability caused by the El Nino Southern Oscillation, the Pacific Decadal Oscillation and the Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation to find the underlying trend.

A heatwave was considered to be five consecutive days with sea-surface temperatures inside the top 10% over a 30-year period.

“There was a clear relationship between the rise in global average sea-surface temperatures and the increase in marine heatwaves, much the same as we see increases in extreme heat events related to the increase in global average temperatures,” said co-author Prof Neil Holbrook from IMAS at the University of Tasmania.

What happens out there, affects here too

The oceans are also a prime driver of on-shore climate, with long-term increased water temperatures affecting the climate of nearby land. Data recently released by the Bureau of Meteorology found that heating of the Tasman Sea directly affected New Zealand’s record breaking summer.

The south Tasman Sea experienced record high temperatures between November 2017 and January 2018, with temperatures between 1.19 °C and 2.12 °C above a 30 year average. By February, the sea had cooled slightly, but were still the second warmest on record (1.09 °C above average).

Mean temperature deciles for Australia, November 2017 to January 2018. Credit: Bureau of Meteorology

This occurred during the hottest Summer on record in New Zealand, over 2 °C above average. Simultaneously, tropical storms (including ex-tropical cyclones) hit New Zealand as they were able to retain characteristics which are usually present over warmer oceans. These storms resulted in large rainfall amounts usually seen in the tropics.

Similarly, south-eastern Australia experiences record breaking high temperatures, with Tasmania averaging 2.05 °C above a 30-year baseline average, and 2.44 °C above average for Victoria.

In discussions about the effect of climate change, it’s vital the central role of ocean and sea temperatures are not overlooked.

“With more than 90% of the heat from human caused global warming going into our oceans, it is likely marine heatwaves will continue to increase. The next key stage for our research is to quantify exactly how much they may change,” said Prof Neil Holbrook from IMAS at the University of Tasmania.

“The results of these projections are likely to have significant implications for how our environment and economies adapt to this changing world.”

The marine heatwave research has been published in Nature Communications