Last updated March 27, 2018 at 10:47 am

A paper published last week in Astrophysical Journal has made some pretty bold claims. According to new calculations, it said, dark matter and dark energy might not exist after all. In a single swoop the paper threatened to overturn nearly 100 years of astrophysics research. However, far from being a revolutionary paper which changes our understanding of physics, other researchers have pointed out serious flaws the findings.

“The claims are completely overblown. The paper makes no predictions for the biggest tests in support of dark matter or dark energy, so it has a long way to go before it overturns what we understand and predict” said Associate Professor Alan Duffy, an astrophysicist from Swinburne University in Melbourne.

The long history of dark matter

The idea of dark matter dates back to the early 1930s and Swiss astronomer Fritz Zwicky. He was working at the California Institute of Technology on the Coma Cluster, a tightly bound group of around 1000 galaxies.

Measuring the velocities of the galaxies, and combining it with classical mechanics and Newton’s theories, he could calculate the mass of the galaxy cluster based on the gravitational force required to hold them all together. Zwicky then compared the amount of light within the galaxy cluster with this required mass, and found that the light-to-mass ratio of the whole galaxy cluster was around 100 times less than nearby stars.

This staggering difference in light-to-mass ratio, he suggested, could be due to the Coma Cluster containing a large amount of matter not accounted for by the light of the stars. He called it “dark matter.”

It took a while for this concept to be noticed, until 40 years later when astronomical knowledge, and importantly, computing power, had advanced.

Princeton University astronomers Jeremiah Ostriker and James Peebles used computer simulations to investigate mass in the universe, and found that the only way they could make our Milky Way galaxy exist was to have more mass holding it together than the mass of the visible objects could provide.

Around the same time Kent Ford and Vera Rubin from the Carnegie Institution of Washington were studying the behaviour of clouds of hydrogen gas in the Andromeda galaxy. These hydrogen clouds orbited the galaxy in a similar way to stars, held in orbit by the cumulative mass of the galaxy within their orbit.

From Kepler’s Laws we know that the gravitational from this central material should be weaker the ever further out you orbit, meaning only ever more slowly moving clouds should still be held in orbit. However, the outer clouds orbited at the same speed as the inner clouds, which would only make sense if there was additional mass in the areas outside the visible galaxy.

In the next forty years, similar observations and simulations have consistently shown the presence of an unseen, as-yet-undetectable mass. The absence of this mass would mean the universe would behave and look wildly different to what we see today.

There is literal mountains of research which comes to the same conclusion – the way that we understand the universe, there must be extra mass that we cannot see. Dark matter, as Zwicky predicted.

New claims of no mass deficit

However a new paper published in the Astrophysical Journal has threatened to overturn that research, by suggesting that there isn’t actually a mass deficit, and therefore dark matter may not exist at all.

Using a new theoretical model, the researchers from University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland claim that the behaviour dark matter and dark energy are supposed to describe can be demonstrated without them. The new model is based on the scale invariance of empty space, or the fact that certain laws don’t change if the distance or energy is altered. In practice, this has been done by adding an additional component to Einstein’s General Relativity.

“In this model, there is a starting hypothesis that hasn’t been taken into account, in my opinion”, says André Maeder, honorary professor in the Department of Astronomy in UNIGE’s Faculty of Science. “By that I mean the scale invariance of the empty space; in other words, the empty space and its properties do not change following a dilatation or contraction.”

When Maeder carried out certain cosmological tests using his new model, including the motion of the outer edges of galaxies as well as clusters of galaxies, he found that it matched real-world observations. However, he also found that the model described acceleration of the expansion of the universe without having to add any dark matter or dark energy. This, it is suggested, means that dark energy may not actually exist as it is not required.

So is 100 years of astrophysics about to be overturned? Other researchers aren’t so sure.

Astronomers point out flaws in claims

“The challenge with this work is that the findings have been greatly overblown, and not by the author who is trying to build successfully on their efforts over the last few years,” said Professor Duffy.

“However, great claims require great proof and we only have a few tests that have been created as ‘toy’ models. To overthrow the required 95% of the universe that appears to exist in either Dark Matter or Dark Energy we would need to see this work be extended to the biggest cosmological tests.” One test which astronomers consider amongst the strongest is recreating the Bullet Cluster, where, following a collision of two galaxy clusters, the distribution of dark matter can be seen by the amount that light is bent by the mass of dark matter – an effect called gravitational lensing.

“The new model in this study supposes that the universe is empty, known as a De Sitter space, which is categorically not the Universe we find ourselves in. That the model explains certain observations in real life is interesting, rather than offering explanations for our situation necessarily.” Duffy also remarked he would like to see a fully developed supercomputer simulation of galaxy formation using this new model.

“It’s hard to understand if galaxies can form to the size and distribution we see around us (using this model) – something that the dark matter and dark energy paradigm naturally gives.”

“Overall, this is a case of media hype inflating the story faster than even the universe can expand.”

Theoretical physicist and blogger Sabine Hossenfelder agreed in her analysis of the research, with a scathing judgement that “the author does not have a consistent theory. The math is wrong.”

She concludes that Maeder “clearly knows his stuff. He also clearly doesn’t know a lot about modifying general relativity. But I do, so let me tell you it’s hard. It’s really hard. There are a thousand ways to screw yourself over with it, and Maeder just discovered the one thousand and first one.”

A long way to go to overturn dark matter

For Maeder’s theory to be true, it would inevitably require a rethink of Einstein’s theory of general relativity. So far, every single test or attempt to try to break general relativity has ended up with the law holding true.

While the new study raises some interesting ideas, by containing apparent flaws in the mathematics and thinking there is still a long way to go before convincing astrophysicists that dark matter and dark energy aren’t required in the universe. They are too fundamental to our understanding of the cosmos, and far more and robust evidence will be required to dent confidence in their existence.

If that evidence were to ever emerge, it would require an entire rethink of everything we know about physics and the universe, and would be the most seminal research in the history of science. But it turns out it takes more than 1 paper and some questionable mathematics to overturn 100 years of research.

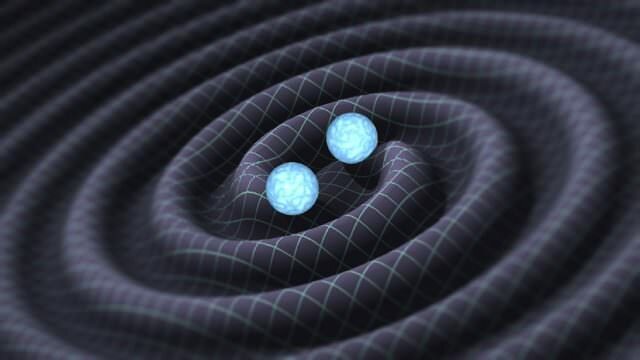

Main image courtesy of NASA, ESA, D. Harvey (École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Switzerland), R. Massey (Durham University, UK) and HST Frontier Fields