Last updated February 21, 2018 at 5:10 pm

First 3D scans show development of Tasmanian Tiger joeys.

Tasmanian tigers got the name for their stripes but their scientific name, Thylacinus cynocephalus, translates to “dog-headed pouch-dog”. That reflects the animal’s remarkable similarity in appearance to canines despite diverging from them on the evolutionary tree more than 160 million years ago.

Tasmanian Tigers, or thylacines, were the top marsupial predators across Australia until their extinction from the mainland around 3,000 years ago, and extinction due to hunting in Tasmania in the early twentieth century.

Related: Tasmanian devils and tigers went extinct on the mainland 3,200 years ago

There are 803 preserved specimens of Thylacines present in museum and university collections all over the world, including 13 of pouch young (joeys).

So far all requests to dissect the preserved joey specimens have been denied, to protect these precious rare specimens.

Scans reveal the structure of all known Thylacine joey specimens

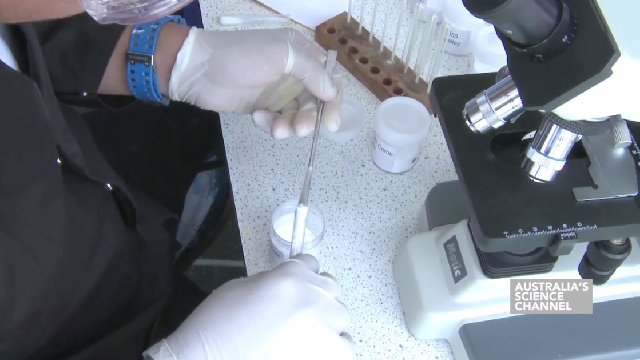

Now, researchers can use non-invasive X-ray micro-CT scanning technology to create high-resolution 3D digital models to reveal detailed structures of the body, including bones, blood vessels and organs.

In a study published in Royal Society Open Science, a research team analysed all 13 of the known samples of Thylacine joeys, including three from Melbourne Museum.

“One of the major advantages of this new technology is that it has enabled us to do research and answer many questions without destruction of the sample specimens,” said Kathryn Medlock, Senior Curator of Vertebrate Zoology at Tasmanian Museums and Art Gallery (TAMG), which also supplied specimens for the study.

Joey development

Tasmanian tigers, as with all marsupials, had pouches to carry their young. Until now there hasn’t been a lot known about the details of their growth and development.

A thylacine pup preserved in ethanol, part of the collection held by the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

The scans revealed that when first born, the Thylacine joeys looked like most other marsupials – a tiny pink jellybean.

Marsupials are born in an almost embryonic state compared to most mammals. And so marsupial young need to be able to find their way into the pouch of their mother and latch onto a nipple.

To do this, these tiny joeys start working out in the womb a few days before birth, excercising their relatively developed forearms to warm up for the climb ahead.

“These scans show in incredible detail how the Tasmanian tiger started its journey in life as a joey that looked very much like any other marsupial, with robust forearms so that it could climb into its mother’s pouch,” says Dr Christy Hipsley, Research Associate at Museums Victoria and one of the lead authors on the study.

“But by the time it left the pouch around 12 weeks to start independent life, it looked more like a dog or wolf, with longer hind limbs than forelimbs.”

Related: Why does a thylacine look like a dog not a tiger?

This research, along with the recently published thylacine genome, provide a starting point for further research about the development of this unique, extinct species.

A case of mistaken identity

Two of the specimens from the TAMG collection were revealed to not be thylacine joeys at all. The are more likely quolls or Tasmanian devils, given the number of vertebrae present and the shape of the bones that support the pouch. This means that there are now only 11 known thylacine young specimens in existence.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to get all the latest science.