Last updated January 9, 2018 at 4:20 pm

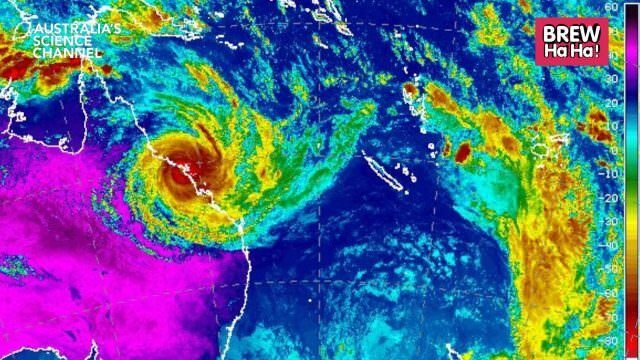

A study published today is the first report using satellite measurements to gauge ice sheet thickness during ENSO variations.

El Niño and La Niña are the two phases of the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), and understanding how Antarctic ice shelves respond to ENSO variability is useful to understand how global climate changes might affect ice shelves around Antarctica.

Front of Getz Ice Shelf in Antarctica. Image credit Jeremy Harbeck, NASA.

“There have been some idealised studies using models, and even some indirect observations off the ice shelves, suggesting that El Niño might significantly affect some of these shelves, but we had no actual ice-shelf observations,” says Fernando Paolo, leader of the study undertaken while he was a PhD student at Scripps Institution of Oceanography.

“Now we have presented a record of 23 years of satellite data on the West Antarctic ice shelves, confirming not only that ENSO affects them at a yearly basis, but also showing how.”

During an El Niño event, associated with warmer water temperatures, researchers expected to see reduced thickness of ice sheets. Surprisingly, the opposite was seen.

“The satellites measure the height of the ice shelves, not the mass, and what we saw at first is that during strong El Niño the height of the ice shelves actually increased,” Paolo said. This is because, as well as promoting the flow of warmer ocean waters to the ice shelves, which can increase melting from below, El Niño conditions also increase snowfall.

Snow is much less dense than ice, and for what the shelves gained in height, they lost five times the amount of mass from the bottom of the sheet in contact with the warmer waters.

Ice shelves melting in Antarctica are bad news for sea-level rise. Not because the ice shelves themselves add much to the rise – they float on the sea. But they act as a buffer to slow down the rate of glacial ice leaving the Antarctic land mass and sliding into the ocean, which has the potential to be a significant contribution to rising sea levels.

This new data set will allow scientists to check if current ocean models match the observed data modelling changes in the flow of warm water under ice shelves, to better help guide sea-level projection rise estimates.

This study was published in Nature.