Last updated December 4, 2017 at 4:51 pm

The extinction of the Neanderthals may have been inevitable, and the result of the sheer numbers of modern humans migrating from Africa to Eurasia, a new model suggests.

Previous studies have argued that a combination of environmental pressure and being out-competed for resources by modern humans drove the Neanderthals’ demise.

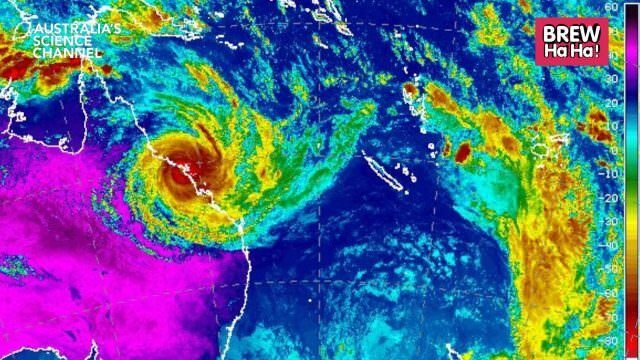

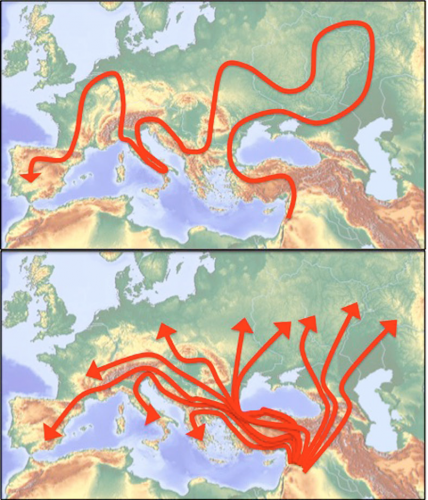

Alternative models of modern humans’ trajectory in Europe. One trajectory, top, or 10 trajectories bottom. The new model realises the dynamics along a single trajectory.

Credit: Kolodny and Feldman.

But a study by Oren Kolodny and Marcus Feldman of Stanford University proposes a model whereby the Neanderthal population was gradually replaced by wave after wave of modern human migration, rather than by a selective advantage.

Over time, as modern humans established themselves in Eurasia, their numbers increased until eventually they represented 100% of the hominin population.

“The replacement of Neanderthals by Moderns seems to have occurred surprisingly fast when compared to archaeological and evolutionary time scales of the two species’ existence,” the study, published in Nature Communications, says.

The two populations in the model are finite, so “all scenarios — apart from the case in which there is no migration between the two demes — inevitably end in fixation of one species and extinction of the other”, the authors write.

“Thus the question is how the probability of each species’ fixation depends on the migration parameters and the carrying capacities of the two demes.”

The study assumes the spread of Moderns into Eurasia was a stepping-stone model where the inter-species dynamics play out on a shifting front of contact.

The authors note that the replacement of Neanderthals by Moderns seems to have occurred surprisingly fast when compared to archaeological and evolutionary time scales of the two species’ existence.

“This may be why many scholars assume that the process was necessarily driven by selection, but whether the process should be considered as having been rapid depends on properties of the model assumed, such as the Neanderthal population size and the expected duration of replacement.”

Kolodny and Feldman’s model takes into account major aspects of the two species’ demography at the time but does not include selection. The authors suggest it may be regarded as a baseline, or a null model, for such an evaluation.

“To assess whether this null model can be rejected in favour of a selection scenario, we study the distribution of replacement durations produced by the model and compare it to the replacement duration suggested by empirical evidence.”