Last updated May 10, 2018 at 11:46 am

Farewell Number 16

Giaus Villosus. Credit: Curtin University

Australia is home to some of the most terrifying and deadly creatures on Earth, and the ones that seem to give most people the heebie jeebies are spiders.

However they usually have a limited lifespan thanks to old-age, shoes, or parasitic wasps which lay their eggs inside the spider.

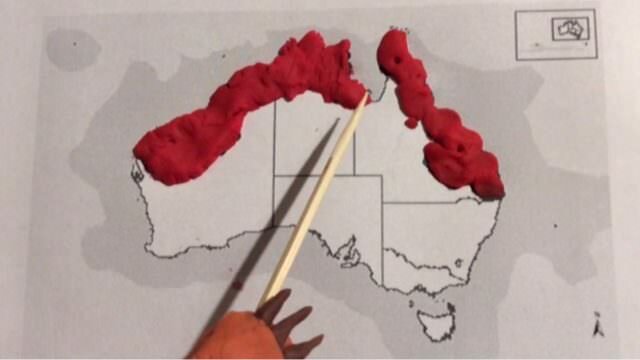

But researchers from Curtin University in Western Australia have announced the death of a spider which rewrites the rules of spider lifespan – a 43 year old female Giaus Villosus trapdoor spider. She takes over the world record from a 28-year old tarantula found in Mexico.

“To our knowledge this is the oldest spider ever recorded, and her significant life has allowed us to further investigate the trapdoor spider’s behaviour and population dynamics,” said researcher Leanda Mason. The spider, with the evocative name of Number 16, was being monitored in the wild as part of a long-term spider behaviour and population study.

Trapdoor spiders are thought to live to around 20 years old, around the same age as tarantulas. However, at 43, we may need to rethink that lifespan.

The life and death of Number 16

The life of the female trapdoor spider is largely spent inside burrows, which they dig themselves after leaving the nest of their mother. As they grow they widen and expand the burrow until they reach full adulthood at about 5 years of age.

The female trapdoor spider will stay in the same burrow for the rest of their life, while a male risks travelling to search for a mate. However, they will never use a burrow created by a different spider, even if that spider has died. For this reason, the researchers can study the behaviour of a single spider by monitoring its burrow.

Number 16’s burrow was first tagged by researcher Barbara York Main in 1974, who monitored the long-term spider population for over 42 years in the Central Wheatbelt region of Western Australia. Tagged at the time as a young spider, the team from Curtin University have continued to monitor Main’s burrows in the intervening years to learn about the spider populations over long periods.

“Through Barbara’s detailed research, we were able to determine that the extensive life span of the trapdoor spider is due to their life-history traits, including how they live in uncleared, native bushland, their sedentary nature and low metabolisms,” said Mason.

As time went on, the spiders in the first 15 burrows tagged died, as well as many spiders tagged since Number 16 (over 150 burrows had been tagged in all). However, Number 16 held on.

At some point in 2016 however, nature caught up with the long-lived spider. “On 31 October 2016 we found that the lid of the burrow of the oldest spider, #16, had been pierced by a parasitic wasp,” the researchers write. They observed the burrow falling into disrepair, suggesting the spider was already dead or parasitised.

“Having been seen alive in the burrow six months earlier, we therefore report the death of an ancient G. villosus mygalomorph spider matriarch at the age of 43.”

The study has been published in Pacific Conservation Biology Journal