Last updated January 11, 2018 at 10:31 am

New Zealand has built its brand on being 100% pure. But currently up to 60% of waterways are so polluted they’re unsafe for swimming. One of the biggest culprits is the dairy industry.

Planting along the edges of streams and rivers helps stop sediment and nutrient pollution. Credit: John Quinn, NIWA.

Diary has boomed in New Zealand recently, increasing from 3.84 million cows in 1994 to 6.49 million in 2015. Those millions of cows produce truly eye-watering amounts of waste.

A single cow can produce 25L of urine a day. That’s a combined volume of 65 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of urine soaking into the pastures of New Zealand every day of the year. This urine is rich in nitrogen. About a quarter of the nitrogen found in cow wee ends up leaching out of the soil ending up in groundwater, rivers and lakes.

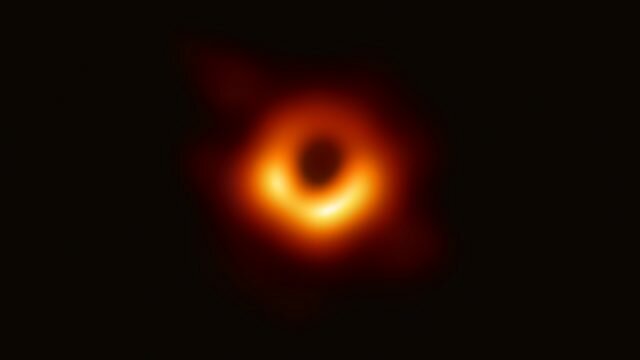

Nitrogen then creates the conditions perfect for toxic algal blooms to occur. These blooms suck up all the oxygen out of waterways, creating havoc for the native plants and animals – 74% of native freshwater fish are considered to be threatened species.

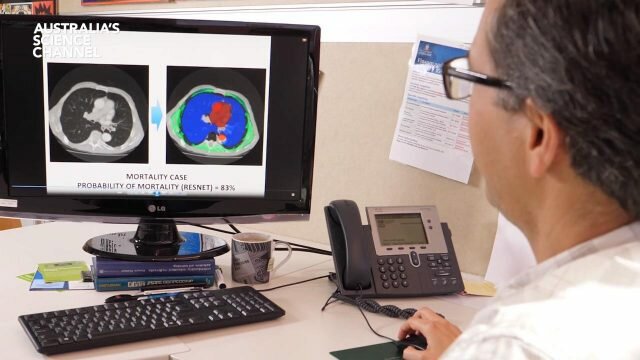

E.coli contamination from cow poos also poses a risk to human health. New Zealand has a reputation for outdoors life, and swimming in natural waterways is part of that allure. The NZ Government wants to make sure that 90% of NZs large rivers and lakes are swimmable by 2040. For now, if you want to check up before you dive in, the recommendation is to check the LAWA website where you can see the results of weekly monitoring for bacterial contamination.

It’s not just swimming that could make you sick. In August 2016, in the small town of Havelock North, over 5,000 people fell ill and 3 people died from a campylobacter outbreak in their drinking water, sourced from a bore contaminated by livestock faeces.

The best solution, say scientists, is to reduce the footprint of agriculture. Smaller herds on less area will improve freshwater quality and have the added benefit of helping New Zealand reach its greenhouse gas reduction commitments.

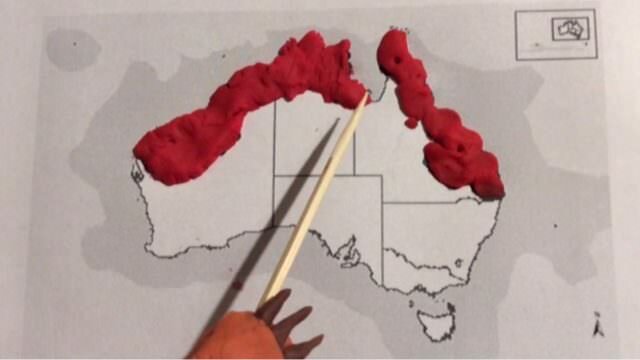

Fences can keep livestock out of waterways, and around 97% of streams running through dairy farms are now fenced. But a fence is no barrier to nitrogen leaching. One approach that is helping reduce the amount of nitrogen ending up in water is to restore ‘riparian strips’.

These are strips of vegetation planted along the edges of streams and rivers, which can prevent sediment and nitrogen from reaching waterways. They also provide shade and habitat for native species, and a recent study found that restoring and managing these areas is worth between NZ$1.7-5.5 billion per year.