Last updated March 1, 2018 at 10:03 am

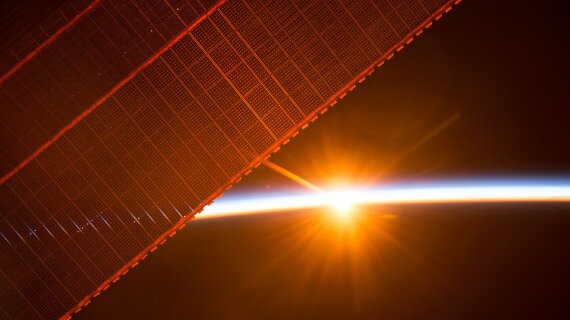

Even if all the countries signed up to the Paris Agreement meet their targets, sea levels are still going to rise between 0.7 and 1.2m by 2300, according to new modelling published today in Nature Communications.

For every five-year delay in mitigation efforts, sea levels will rise 0.2m, emphasising the need for action in the coming decades, say the researchers from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

Related: Sea-level rise is accelerating

What do the experts think?

Associate Professor Pete Strutton is a biological oceanographer at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania and at the ARC Centre of Excellence for Climate Extremes

“This is exactly the kind of work that people need to hear about.

We need to realise that climate change is happening. Even if we stop emitting today, the effects of our past emissions will be felt for centuries to come and every year that we delay action has consequences for the future.”

Distinguished Professor Bill Laurance is Director of the Centre for Tropical Environmental and Sustainability Science, James Cook University

“This study tells us it’s time to put our money where our mouth is. I think we should encourage all the climate skeptics and big fossil-fuel investors to live smack on the shorefront.

That way, if they’re right about climate change, they’ll be happy as clams. But if they’re wrong, they can just live with the clams, and then let’s see how happy they are.”

Ian Lowe is Bragg Member of the Royal Institution of Australia, Emeritus Professor of Science, Technology and Society at Griffith University, and former President of the Australian Conservation Foundation

“This paper is yet another reminder that climate change is already a serious threat to coastal communities. Sea level rise and storm surges will be a real problem for those living in coastal areas, as well as threatening nearby infrastructure, including several of our airports.

Displacement of island communities in the Pacific will inevitably be a social and political issue for Australia.

These considerations underline the need for an urgent and concerted initiative to decarbonise our energy supply and improve the efficiency of using energy, since the scale of the problems will be directly determined by the effectiveness of our policies to implement the Paris agreement.

At this stage, our national response is totally inadequate.”

Professor John Church is from the Climate Change Research Centre at the University of New South Wales

“With the order of 100 million people living within 1 m of current high tide level, the world is vulnerable to rising sea levels. More people are moving to live within the coastal zone, increasing the vulnerable population and infrastructure. Recent sea level data show that the rate of sea level rise is accelerating, further increasing the potential vulnerability.

This paper shows:

- That, even with the most stringent greenhouse gas mitigation, the central estimate of sea level rise by 2300 is more than 0.7 m and still rising, with a potential rise of twice this amount. These results mean that adaptation to sea level rise will be essential.

- Delaying mitigation results in a higher projected sea level rise by about 20 cm for every five year delay. Mitigating to achieve net zero carbon dioxide emissions rather than zero greenhouse gas emissions results in a substantially higher central value of projected sea level rise, with a potential rise of metres by 2300. To avoid larger sea level rises, mitigation is urgent.

- Under the Paris Agreement, current mitigation commitments by nations to 2030 are at the upper level of the emission scenarios considered. Mitigation efforts will need to be increased significantly and urgently if a rise of more than 1 metre sea level rise by 2300 is to be avoided.”

Dr Xuebin Zhang is a Senior Research Scientist for CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere

“Global warming and sea-level rise are two important indicators of anthropogenic climate changes, but the ocean and atmosphere respond very differently to greenhouse gases emission mitigation, e.g., as proposed under the Paris Agreement.

The atmosphere can respond very quickly to emission cuts and global mean surface temperature can stabilise or even reduce, while the ocean takes a much slower pace and adjusts on the timescale of a few centuries, which means that global sea level is guaranteed to rise in coming centuries, even under the strong mitigation to meet temperature targets set by the Paris Agreement.

This is an interesting study, by quantifying sea-level rise until 2300 and its sensitivity to the pathway of emissions during this century. The very insightful finding from this study is that it clearly analyses, in a quantitative manner, the benefit of earlier mitigation, i.e., lower median sea level rise and much reduced risk of a low-probability, high-end sea level rise scenario by 2300.

So our near-term action in coming decades will impact the long-term sea level rise, and society needs good guidance from studies such as this for adaptation and mitigation planning for future sea-level rise.”

Professor Charitha Pattiaratchi is Leader at the Australian National Facility for Ocean Gliders (ANFOG) and is from the Oceans Graduate School & The UWA Oceans Institute, University of Western Australia

“This interesting paper examined global mean sea level rise and conclude that the global sea levels will rise between 0.7 and 1.2 metres by 2300 in response to different emission pathways.

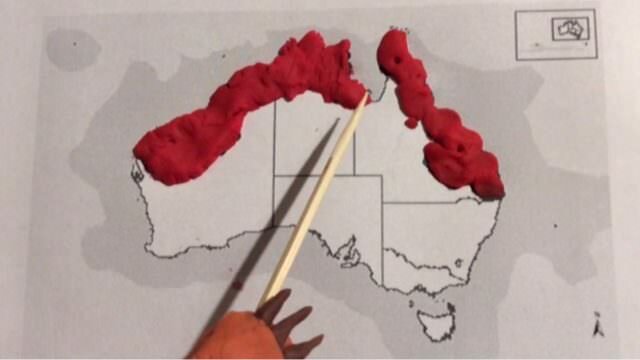

However, a similar sea level increase could occur within the next decade due to a combination of nodal tides and the El Nino Southern Oscillation effects irrespective of mean sea level rise due to global warming. The nodal tides are due to changes in the Moon’s orbit that occur every 18.6 years.

Currently we are in the low part of this cycle and in south-west Australia – over the next nine years the sea level will increase by 0.25 m due to this effect alone. This increase in water level due to tidal effect over the next 10 years is higher than that observed over the last century (0.15m).

Similarly, La Nina events increase the mean sea level by up to 0.30 m for a total mean sea level rise of 0.55m.”

Associate Professor Grant Wardell-Johnson is from the ARC Centre for Mine Site Restoration and School of Molecular and Life Sciences, as well as President of the Australian Council of Environment Deans and Directors (ACEDD), and from Curtin University

“This is just another article building the mountains of information quantifying the necessity for society to act.

Yes and it’s another important study clearly articulating the seriousness of delayed action on human-generated climate disruption.

This comes out a few days after we learn about the green light given by government to increases in greenhouse emissions from nearly 60 Australian industrial sites. This cancels out the hundreds of millions of dollars spent on emissions cuts under the coalitions Direct Action climate policy.

So-called Direct Action by society means we spend some money – but we are keep the status quo. And the status quo means very serious disruption to humanity this century.

We all know where this will end. So we are all partying instead of acting. If it was imminent war threatening our survival – society would be united against the threat – led by leaders with a sense of genuine purpose and vision.

But it’s much more serious than war. This article is about sea level rise – but there is now ample evidence and regular updates as the details of the seriousness of humanities situation becomes ever clearer.

This is not just an article to scare the people in harbour-side mansions. If a major proportion of the world’s population is displaced, it is a problem for everyone. And there is plenty known about the delayed impacts of current emissions inland. Let alone keeping emissions full steam ahead.

Expert comments gathered by the Australian Science Media Centre (AusSMC)