Last updated January 11, 2018 at 10:33 am

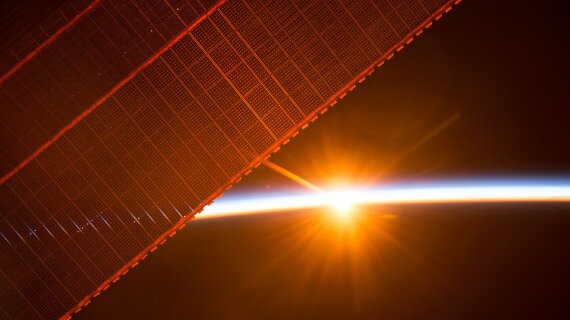

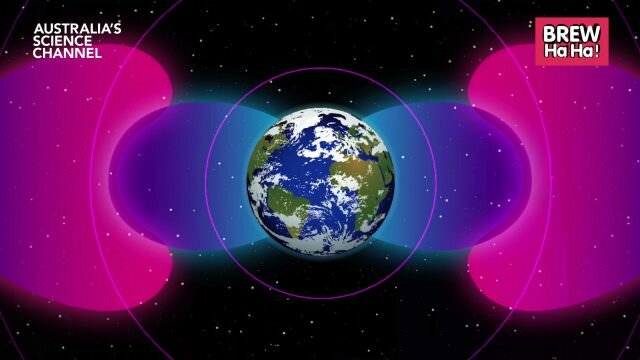

Thousands of light years away a star meets its end, exploding as a supernova. Cosmic rays spew out of this cataclysmic event, streaming across the universe unimpeded and unchecked. And when they reach Earth, according to Danish researchers, they might cause clouds to form.

However, claims that these clouds are significant factors in climate change are exaggerated, say other scientists.

Image credit H. Svensmark/DTU

Cosmic rays are streams of high-energy particles released from stars, supernovae, and the corona of our sun.

When they reach Earth these highly energetic particles interact with molecules in the Earth’s atmosphere and can knock an electron free from the atom.

According to new research, this process, called ionisation, can lead to a process of reactions resulting in a condensation nuclei – the seeds around which condensation starts, and ultimately a cloud.

Cloud condensation nuclei are formed by the growth of small molecular clusters called aerosols, made up of mainly sulphuric acid and water molecules.

The research by Henrik Svensmark from the Technical University of Denmark has shown, theoretically and experimentally, that the ions caused by cosmic rays can combine with these aerosols, accelerating their growth in size and making them more stable against evaporation. The larger aerosols are then more likely to become condensation nuclei around which water can condense, and clouds form.

Although the ions are not the most abundant particle in the atmosphere, electro-magnetic interactions between ions and aerosols make fusion between ions and aerosols much more likely. The researchers estimate that even at low ionization levels about 5% of the growth rate of aerosols is due to ions. In the extremely rare case of a nearby super nova they claim the effect could be more than 50% of the growth rate.

In the accompanying press release however, and mirrored in some reporting, Svensmark added some exaggerated claims about the role this process plays in climate change that were not supported by the research itself. These included claims that the research was “the last piece of the puzzle explaining how particles from space affect climate on Earth.”

It also claims that the process could have affected several historical periods of altered climate by multiple degrees.

However, other scientists say that, while the formation of cloud condensation nuclei might be interesting for climate change modelling, the claims around the role in climate change included many oversimplifications and couldn’t be backed up by the research.

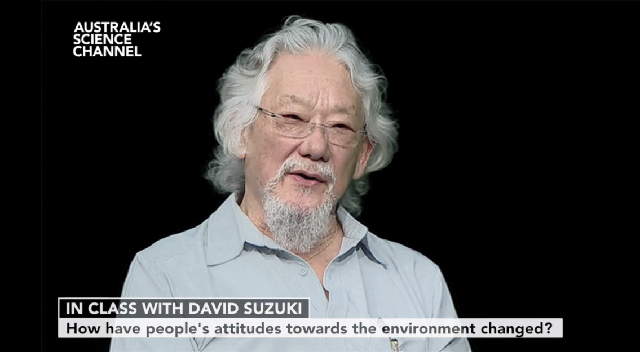

“The exact impact of cloudiness on climate change is a little foggy,” says Nate Byrne, an ABC weather presenter who was formerly a Royal Australian Navy meteorologist and oceanographer.

“In essence, clouds can prevent heating, or may compound it – it depends on the type and distribution. For example, low water clouds can trap heat like a blanket but also tend to rain, which can evaporate and cool the surface…it’s a big mix of factors.

“The role the ions play in creating cloud condensation nuclei (CCN) is what’s being studied here, but they seem to then make a lot of extra claims in the press release that the research doesn’t address. For example, simply having CCNs present doesn’t necessarily mean more clouds – you also need to have an atmosphere which is saturated with respect to water vapour.”

Overall Byrne had few issues with the research into CCN production itself, however the press release’s claims of significance in climate change raised questions and he felt weren’t justified based on the research.

“It will help us build better models of what the climate may look like in the future, and improve our understanding of natural variation. The research doesn’t catastrophically break our understanding of recent climate change or its causes (despite what the media release may obliquely suggest) – it’s more of a seasoning than a main ingredient.”

Hamish Gordon, from the Institute for Climate and Atmospheric Science at the University of Leeds, and who works on a similar experiment at CERN called CLOUD was similarly unconvinced by some of the wild claims about the contribution to climate change.

“The press release (from the Technical University of Denmark) states that about 5% of the growth rate of new aerosol can be due to ions, which is the main result of the article. Of itself, this is an interesting and plausible result, and if it stands up to more detailed scrutiny it may prove an important contribution to aerosol microphysics.

However, it is very far from “the last piece of the puzzle explaining how particles from space affect climate on Earth.”

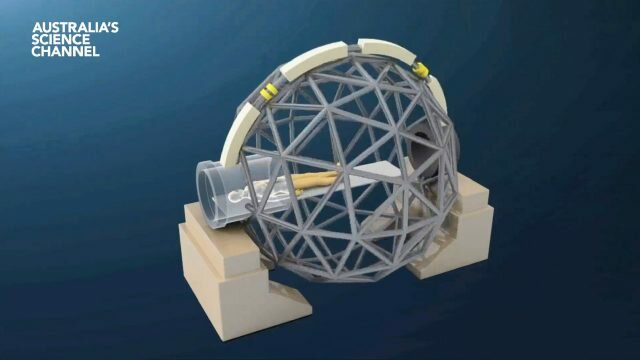

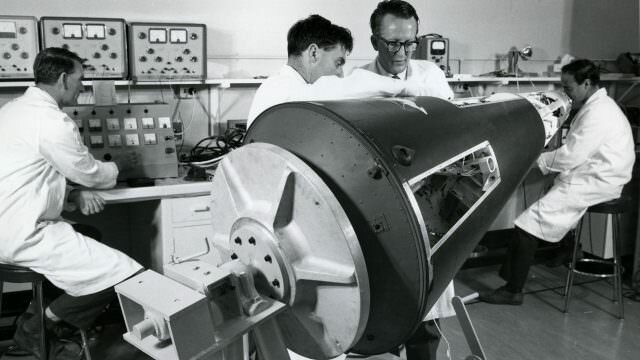

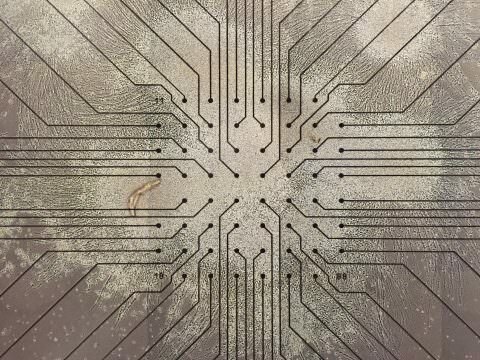

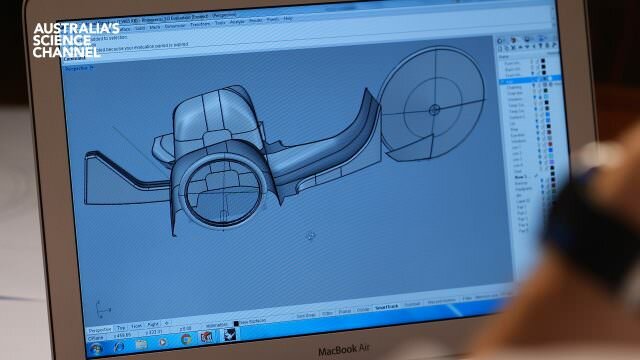

The CERN CLOUD Chamber. Image credit CERN

Gordon’s research as part of the CERN CLOUD experiments has contrasted with Svensmark’s conclusions. Gordon and his colleagues used the CLOUD (Cosmics Leaving Outdoor Droplets) chamber to measure rates of nucleation involving sulfuric acid, ammonia, ions, and organic compounds.

The experiments and observations of the atmosphere showed that nearly all nucleation that occurs in the atmosphere involves ammonia or biogenic organic compounds, in addition to sulfuric acid.

And while ions do contribute to that nucleation process, the success of the process doesn’t depend on their concentration. From their results, they concluded that “variations in cosmic ray intensity do not appreciably affect climate through nucleation in the present-day atmosphere.”

On the current study from Svensmark, Gordon added “As most of the particles end up sticking to existing cloud seeds rather than forming new ones, only a small fraction of ions end up making a difference.

“In today’s atmosphere, ion concentrations only change by a few percent every few decades. While the effects on particle growth studied in this article were not accounted for in previous atmospheric modelling studies, the effects the authors find are actually quite small – 5% will make relatively little difference.”

He said the effects of changing ion concentrations on cloud seeds were negligibly small in the present day atmosphere.

The caution from scientists about the extravagant claims in the press release are based on history.

Svensmark has previously published on the topic of “cosmoclimatology” before, and his research has been used by climate deniers to doubt the influence of carbon emissions.

Indeed other scientists have repeatedly pointed to his claims as being exaggerated, and studies have found the contribution of cosmic rays to global climate change to be less than 10%.

While the process described in this study is interesting and does describe an interesting link between solar radiation and the formation of cloud condensation nuclei, in a lab at least, it is not likely to be a major contributor to climate change affecting Earth.

There is more to discover around the effect of cosmic rays, charged particles and the atmospheric conditions, however, according to the mountainous amounts of the best evidence available, climate change is still driven by human-produced emissions.

And the whole story highlights once again the dangers of making overreaching claims of the significance of research in press releases.

The research was published in Nature Communications