Last updated March 9, 2017 at 8:47 am

Originally presented at The Storytelling of Science by Science Nation, Wednesday 6th April 2016.

My parents owned War of the Worlds, the musical version, on LP. I can’t emphasise enough how much this music both fascinated and scared THE CRAP out of me as a child. Accompanied by some incredibly terrifying album artwork that seared itself onto my brain, it was my first experience as a child to the world of aliens in pop culture. Something I took forward through my teenage years where I became an X-files obsessive. People have always been fascinated by the possibility of life on other planets. What fascinates me now, as a science communicator, is what would happen if we ever actually found any – how would the world find out?

Let me first take you back to New York, on a hot Tuesday afternoon in 1835 where for a penny you could pick up a copy, hot off the steam-powered press, of The New York Sun and read within of the incredible new telescope of Sir John Hershcel. Now some of you may have heard of Herschel, who was indeed an English astonomer, who had very much set off for South Africa in 1834 to observe the southern skies, with what was one of the most powerful telescopes to date at that point. The Sun breathlessly reported over 6 days observations from the telescope, which when pointed at the moon not only detected signs of water and vegetation, but creatures ranging from bison and goats, to bipedal beavers which “carry their young in their arms like a human being, and move with an easy gliding motion”. But the real surprise came on day 4 of the reports when bat-like creatures, that could fly, and looked like “innocent and happy creatures” were seen.

The reports caused a huge amount of excitement upon publication, along with immediate scepticism. But for weeks the story was recirculated and picked up and repeated by other news outlets. It’s now known as the Great Moon Hoax of 1835 and is what some consider the first mass-media event. What it did NOT do, is cause mass panic or hysteria.

Unlike the story you have probably hear of the other famous hoax….the broadcast of Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds a play performed as a simulated real-time news bulletin reporting a martian invasion. Broadcast on CBS in 1938, the play caused mass panic as people mistook the program for real news. But the extent of this mass hysteria seems to have been overblown, with a lot of modern sociologists and historians saying that while some people were definitely fooled by the broadcast, few panicked and it definitely wasn’t the widely held nationwide hysteria of popular myth.

So what would happen in reality? Let’s go through two scenarios – one which is really exciting but highly unlikely – i.e. detecting intelligent life, and the other scenario which I think is inevitable and just as significant – detecting some form of microbial life.

So what would we do if we detected intelligent alien life?

We might first find it through SETI – the search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence, which has been around for over 50 years now. They have thought about this, there is a plan and it’s very impressively called the SETI Declaration of Principles Concerning Activities Following the Detection of Extraterrestrial Intelligence, commonly known as the SETI protocol.

- First on the SETI protocol is verify your signal, independently and from multiple observers to confirm that what you’re picking up is real and not an artefact or hoax.

- Once other groups have confirmed the the signal, the original astronomers then start notifying people like their national authorities and other observatories around the world.

The guidelines also account for the United Nations’s 1967 Space Treaty, which means that the discovering astronomer also alerts the United Nations via the UN Secretary General to the discovery. - Once all this is done, the astronomer who discovered the signal also has the privilege of making the first announcement to the public.

In theory. What would happen these days? The signal would have it’s own parody twitter account before you can say “extraterrestrial”.

And a big challenge for any science communicators will be trying to explain the level of credibility of a detection. It’s not going to be a known 100% genuine detection, so how do we convey uncertainty? There’s actually a proposed scale for this called the Rio scale (in much the same way we have something like the Richter scale for earthquakes). The Rio scale ranges from zero – for a hoax or error, while a ten would indicate we’re sure we’ve confirmed genuine communication from an alien civilisation. Any detection might start low on the Rio scale and rise as more evidence is gathered, but this process could take years.

Interestingly, the SETI protocol does state, unambiguously that we should not attempt to reply to the message.

So there is a protocol – and there have been a couple of times it could or should have kicked into gear with a couple of false alarms.

In 1967, a young PhD student in England recorded a regular pulsating signal using a radio telescope. Jocelyn Bell (now Bell Burnell) was that young astronomer, and the signal caused real consternation when it was initially found. An early theory was that the pulses might be coming from an interstellar beacon and the source was tentatively catalogued as LGM, for “little green men.” Instead it turned out she had detected pulsars – a highly magnetized, rotating neutron star. In fact just this week we’ve discovered a new one in our neighbouring Andromeda galaxy.

Way back in 1997 SETI scientists thought they had detected something, before anyone could verify independently, within 24 hours, they’d had a call from the New York Times. And that was in the deep dark ancient past. BG. Before Google. Dial up days. Imagine how fast the news would travel today.

Even in Australia we’re not immune from our own strange signal detection. Last year it was announced that strange signals detected at Parkes were not short radio busts from another civilisation but someone opening the microwave on their lunch before the timer went off. Although to be fair, no one did actually think these were alien signals!

So if it’s not another intelligent civilization:

What kind of life might we be most likely to detect and how would we do it? Most likely the first sign of astrobiological life will be microbial. If it has similar chemistry driving life to that here on earth, there are a couple of ways that we could detect it.

- Curiosity digging through the dirt on Mars which we now know may contain running water for part of the year. As an aside- that was where I inititially started tinking about this idea of what science communication would look like. Curiosity has already detected a lot of the chemical ingredients needed for life: sulfur, nitrogen, hydrogen, oxygen, phosphorus and carbon. For now, Mars mission planners avoid landing sites that might have liquid water, even though those are the sites most likely to have life, as part of the “planetary protection” requirements of the Outer Space Treaty to avoid contaminating other planets with life from Earth.

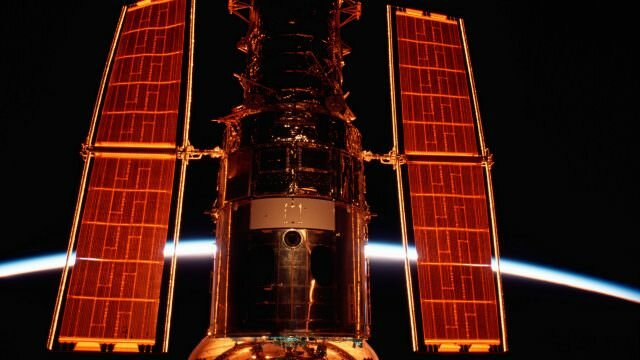

- The second option is the James Webb Space Telescope to be launched in 2018 – which could detect gases that might indicate some sort of biological process occurring – like methane or oxygen located in an exoplanet’s atmosphere simply by observing the reflection of light.

And how will the media react when we detect perhaps the less sexy but still epoch changing news of space microbes? Well, let’s have a look because there’s been a few stories within the last few years that have reported exactly that. The first was from 2 years ago where researchers who released a balloon into the stratosphere claimed to have found diatoms – single-celled algae that they claim did not originate from earth. The claim was quickly debunked.

Another claim that got quite a lot of coverage in 2011 was a claim by a NASA scientist contained ‘bacterial fossils‘ – a red flag on both of these reports is that they were published in the Journal of Cosmology which although ostensibly a peer reviewed journal has a bad reputation for these sort of claims. In both these cases the news was reported widely, but the immediate following scepticism meant that there were no large social impacts of the news in terms of humans seriously having to reconsider our place in the cosmos.

So I’m still waiting – perhaps when we visit Europa, or when we send another robot to Mars – just this week they’ve identified a new site the Argyre basin, which researchers think could be a contender for signs of martian life. I can’t wait for the news to finally be real, because there won’t be a more exciting time to be a science communicator.

Because a talk on the universe and whether we’re alone wouldn’t be complete without a Sagan quote, I’ll leave you with this gem:

“The Universe is a pretty big place. If it’s just us, seems like an awful waste of space.”

Written by Lisa Bailey

Did you like this blog? Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to get all the latest science.